What is a ditty? To denizens of the early 20th century, the term refers to a bag or box (illustrated above) in which necessaries or treasures are stored. To those involved in the modern music industry, it can refer to a person who specializes in angry, debasing, or otherwise insulting poetry set to industrial noise, having taken on a variant of the term.

In music, a ditty can mean either a simple tune, or otherwise to simple words sung to a simple tune. To those of us who spend most of our time buried in the context and details of ancient music, in historical usage a ditty referred to a sung poem or the lyrics to a song.

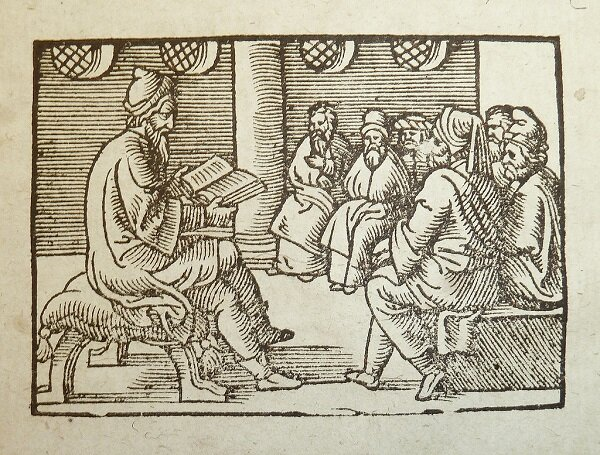

… , dittie , dictie , etc. (Lat. dictum, dict , a saying) . In ME, ditty denoted a composition or treatise and then a piece of verse; by the 16th c., it had come to mean the words of a song. As a verb, ditty could mean to sing a song or to set words to music—now obsolete. In Thomas Morley ’s Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practical Musicke ( 1597 ), the section on how to fit music to a text is titled “Rules to be Observed in Dittying,” and Samuel Daniel in A Defence of Ryme ( 1603 ) remarks that feminine rhymes are “fittest for Ditties.”

– Edward Doughtie, The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4 ed.)

We encounter the term in John Dowland’s Second Booke of Songs or Ayres (1600), where in the table of contents, the twentieth song is titled, “Finding in fields my Siluia all alone.” But turning to the correct page, we find a note “for Finding in fields : ye shall finde a better dittie.” The Second Booke was printed in London by Thomas Este while Dowland was serving at the court of Danish king Christian IV, hence Dowland’s Dedication, “From Helsingnoure in Denmarke the first of Iune. 1600.” Did Dowland decide on a “better dittie” or did the printer decide he had seen enough drivel concerning nymphs and shepherds, making the substitution on his own initiative?

As 21st-century artists, we are accustomed to having very little control over the disposition of our music, with streaming platforms taking the lion’s share of profits (we typically get $0.0004 per stream). But in 1600 it may have been even worse. Dowland sold the rights of his songbook to the printer, at which point he no longer had control over the contents, nor did he receive royalties from sales. If Thomas Este made the substitution, he was complicit in the creation of “Tosse not my soule,” one of Dowland’s best songs, with suitably melancholy lyrics and full of counterpoint and biting dissonance. It was still Dowland’s music, but thank you Thomas Este.

The good news is that you will soon be able to hear our interpretation of the “better dittie” as we are just now finalizing our new album, The delight of solitariness, Lute songs and solos of John Dowland. We have chosen a program consisting of some of Dowland’s lesser-known songs, and we’re pleased with the result. Watch this space.

The “New” in our title is not exactly accurate in this post. The fact is, in fourteen years of blog posts, we seem to have covered so many aspects of early music in modern culture that it is hard to improve upon what has already been presented. But the topic of class is—and should be—mentioned, discussed and highlighted as often as possible, particularly in view of the increasing divisions we are seeing in this time of rapidly increasing censorship on the internet. Pundits and political figures appear to be ramping up their intensity on the variety of petty issues that are turned into points of division among people. When it comes down to it, many of the petty issues dissolve when the more pertinent issue of class rises to the fore.

Early music, and the lute in particular, has limited appeal to persons who are or choose to dwell outside the fortress walls of the academic/leisure class. We propose that is the primary reason popularity in early music is in decline. Below is a reposting of an essay we shared nine years ago, and it is perhaps now more pertinent than ever.

April 4, 2015

Let’s not mince words: Early music bears NO ancestral relationship to what today’s historians and hype-merchants market as “classical” music.

Early music was always functional music of some sort, whether composed for devotional or liturgical purposes, social dancing, entertainment for wealthy patrons, as a domestic pastime, as a theoretical exercise, or as the common indulgence in the craft of converting clever poetry into song. Most music from as late as the mid-16th century survives only in handwritten manuscript form. Naturally, when the printing press and moveable type made published music available to a larger audience, the printed music was costly and only available to the very wealthy elite. Astute composers and ambitious publishers began to take advantage of the potential for financial gain through sales to the nobility and the nouveau riche. But composers invariably sold their rights to the publishers for a pittance and made very little from the sale of the always relatively small print runs of their music. And, when reading through the the prefaces and deferential dedicatory remarks, nearly all our composers mention that the music was written during idle hours and only meant for private consumption.

What we know as “Classical” music was always composed with marketing in mind. From the 18th century onward, church music became something quite grand, and both Protestant services and the Catholic Mass were celebrated with rather large orchestras and choruses, with obbligato instrumentation and including motets with highly ornamented vocal passaggi. In the world of secular entertainment, large-scale theatrical productions and public concerts were produced on a regular basis in hopes of financial success in the form of ticket sales. Even in the realm of domestic chamber music, etudes, sonatas, and small-scale instrumental ensemble works were composed, published and blatantly distributed widely for financial remuneration.

Even though what we have come to call classical music was originally created by primarily young and mostly starving composers, at least in the US, today’s classical audiences are not exactly drawn from the ranks of what you might call the working class. Audiences for classical music pride themselves on participating in an art form that caters to an elitist upper class.

“Why shouldn’t we be elitist…Classical musicians represent some of the finest talent on Earth. They spend a lifetime working tirelessly to perfect their craft. We should celebrate that phenomenon, making classical events a special, elite experience.”

– Norman Lebrecht, from Reframing the Classical Music Experience, keynote address at the Dutch Classical Music Meeting, Oct. 2011

Despite the fact that many early music performers, including Frans Brüggen, began their careers deliberately thumbing their noses at the entrenched world of classical music, today’s early music promoters have somehow morphed their PR materials to emulate their once maligned models, opting to target the same old white elite upper class audience, resulting in a depiction of early music as low-calorie classical music that is really something better than it sounds.

As for attracting young working-class audiences with less disposable income, generic classical music has become a weapon of class disruption, with recordings of Mozart’s greatest hits blasted loudly in public spaces in order to discourage loitering youth:

Classical music has thus been seized upon by Transport for London and a host of other business and government leaders, not as a positive moralising force, but rather as a marker of space: a kind of “aural fence” or sonic wall, signalling “inclusion to some and exclusion to others” through its culturally conditioned associations: white, old, rich, elite.

This amounts to an orchestrated campaign of what French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu termed “symbolic violence”: the use of cultural forms by the powerful to at once assert and legitimise their domination. As one commentator notes, the dangerous message this sends to young people is: “1: You are scum; 2: Classical music is not a wonder of the human world, it is a repellent against anti-social behaviour”.

from – Theo Kindynis, “Weaponising Classical Music: waging class-warfare beneath our cities’ streets,” Ceasefire, Saturday September 29, 2012

When early music experienced a 20th-century renaissance, it was revived by curious historians and creative composers who saw something of interest in older music, which was nearly always considered to be a mere precursor of the later monumental works, or perhaps a source of inspiration for something new and more elaborately developed. Musicians who embraced the early music revival were, for instance, conservatory-trained violinists who did not possess the chops to play the Tchaikovsky concerto (see introductory remarks by Ernst Meyer, in Early English Chamber Music, 2nd rev. edn. ed. Diana Poulton), but they approached the music as a simpler, undeveloped subset of classical music.

The fact remains that, in functional terms, early music bears a closer ancestral lineage to 20th-century popular music by Gershwin, Kern, Straythorn – much of it conceived as either good musical settings of poetry or as functional dance music – than it does with Mendelssohn or Mahler. Early music is more akin to the music of top singer-songwriters like Joni Mitchell, John Lennon, or instrumentalists like George Van Eps, than to the aural assaults composed by Wagner, or the dripping, vibrato-laden romantic music favored by some of our more famous violinists. And how many of our more prominent lutenists who started on classical guitar play with a plodding technical precision, replete with Segovia-like gestures, rather than placing emphasis on shaping the lines like the vocal polyphony that inspired much of the best lute music?

Classical music seems to have annexed early music as a sub-category, or rather ingested the genre like a whale tucking into so much plankton; or the way Home Depot took over the local hardware shops where one might find something unique on the shelf rather than packaged in shrink-wrap. Or the way Walmart displaced the local grocery where one could chat with the grocer and buy three slices of a different type of cheese.

Conservatories with early music programs are missing the point by teaching using the same format and structure as classical repertory. Historically appropriate early music courses should teach improvisation, transposition and playing and singing by ear with a natural voice:

“For from a feigned Voice can come no noble manner of singing; which only proceeds from a natural Voice…”

– attributed to Nicholas Lanier, An Introduction to the Skill of Musick, by John Playford, London, 1674.

Early music courses should embrace the traditions from which the music originally evolved, not through the conventional coursework of the conservatory. And if early music is to survive as a genre worth preserving, it will be because it has inspired musicians young and old who empathize with the oral-aural tradition. It will be because of the music’s honesty, its intimacy and its directness, and not because it is marketed towards the deep pockets of ageing elitist classical music audiences indulging in a low-brow lark.

After fourteen years of sharing a panoply of Unquiet Thoughts, we pause to reflect on some of the major themes running through our series of quotations and essays. The primary focus of this series has always been to highlight our work in preserving the essence of early music in our modern age, and pointing out why that might be worthwhile. But we also like to offer commentary on the state of our shared planet, our observations on fallen empires, and our understanding of historical precedents that may help explain how we got to where we are today.

While most of our activity of late on Unquiet Thoughts has been devoted to recordings, we would like to offer our readers a taste of our old format. A device we have employed in the lengthening shadows of this blog’s past is sharing quotations from the vast collection of reading material that fills floor-to-ceiling shelves and accumulates on every available surface—what we call the Mignarda Reading List. We may be unusual in today’s world in that don’t have a television in our house. Instead, we read books.

Below is a handful of quotations that outline some of the themes of our blog, drawn from our current reading list with examples that include books, journals, and other miscellaneous scribblings.

Music, Science, Time, and Polyphony

“The heavenly motions are nothing but a continuous song for several voices, to be perceived by the intellect, not by the ear; a music which, through syncopations and cadenzas as it were, progresses toward certain pre-designed six-voiced cadences, and thereby sets landmarks in the immeasurable flow of time.”

– Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630), Harmonices Mundi Libri V, 1619

Harmony

“It is harmony that causes the entire world to exist and that spreads itself throughout the universe, and without harmony all the elements and nature would soon be dissolved. The harmony that is born of these different elements only takes shape through their contrasts with one another, just as the harmony that caresses our ear so sweetly is formed by the difference between the voices or the instrumental sounds.”

– Mercure galant, 1680, from Patricia Ranum, The Harmonic Orator, Pendragon Press, Hillsdale, 2001.

Feudalism

“In general, one can say that a feudal state is one in which all the members of the ruling class form a feudal hierarchy with a chief lord or suzerain at its peak…among the feudal monarchies, it is necessary to say that all that is required to make a feudal state into a feudal monarchy is to have the suzerain bear the title of king.”

– Sidney Painter (1902 – 1960), The Rise of the Feudal Monarchies, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1951, p. 4.

Our secular age

“…[T]he avowedly secular culture of today turns out upon close examination to be either a pantheistic religion which identifies existence in its totality with holiness, or a rationalistic humanism for which human reason is essentially god, or a vitalistic humanism which worships some unique or particular vital force in the individual or the community as its god, that is, as the object of its unconditioned loyalty.

– Reinhold Niebuhr (1892 – 1971), The Essential Reinhold Niebuhr, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1986, p. 80.

What makes a university?

“I cannot begin to tell you what it means to me to have my name on the library. I have said over and over again that it takes two things to have a decent university: professors and a library. Presidents, provosts and deans do not make universities. Information that coverts to knowledge that then coverts to wisdom (one would hope)—those are the things that make universities. I am thrilled to be a part of the real university.”

– Michael Schwartz (1937 – 2024), President emeritus, Cleveland State University

Hello. Is anyone there?

“There’s no reason to be walking around with a mask. When you’re in the middle of an outbreak, wearing a mask might make people feel a little bit better and it might even block a droplet, but it’s not providing the perfect protection that people think that it is. And, often, there are unintended consequences — people keep fiddling with the mask and they keep touching their face.”

– Dr. Anthony Fauci

We are pleased to announce the official release of our new album, Shakespeare’s Lutebook, on the Prima Classic label, and it is now available as a complete album for streaming and download—physical CDs are also available directly from the artists.

Prima Classic has been releasing featured tracks one at a time in digital format over the last few months, which has been a new concept for us as artists. But the incremental release has given us the opportunity to offer more interesting background and historical information on each track, as well as in-depth discussion that details our interpretive choices. The album download comes with a pdf link where listeners will find extensive liner notes and descriptive details of each track.

Music in Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s First Folio, published in 1623, bears a dedicatory poem by Ben Jonson, “To the memory of my beloved,” writing that the plays of Shakespeare were “not for an age but for all time.” While Shakespeare’s work is indeed timeless, it was very much of his own age, and the plays reveal a great deal of contextual detail concerning Elizabethan life, customs, manners, and music.

References to music in the plays appear as 1) stage directions for music, often flourishes for entrances; 2) songs, where action stops and a song is sung to a text that is given; 3) fragmentary songs interwoven into dialogue, often as banter; and 4) witty allusions to songs or ballads to reinforce a passage or, frequently, a pun. That musicians took parts in original productions of the plays is certain. Characters appear at certain junctures in many plays for no other apparent reason, and then music is called for. The explanation must be that the otherwise incidental characters were musicians making an entrance to assist in performance of a song or dance, instrumentally or vocally. Outdoor productions at the Globe Theatre most likely did not feature music played on lutes, and it may be assumed that louder instruments were used and probably played with less delicacy than one associates with such a refined instrument. But indoor productions at Blackfriar’s most likely included lutes, if only to be broken over a character’s head.

Shakespeare scholars have sifted through every word of every play and have shared sometimes pointless speculations on what the texts may mean to modern readers. But the many earnest analyses that explore such modern concepts as Freudian angst and gender (in-) sensitivity can never fully scrub away the contextual grime concealing layers of meaning hidden within the texts of songs and ballads. In order to convey any music effectively, today’s performers must delve deeply into

song texts with a thorough understanding of historical musical gesture. Specialists in Elizabethan lute songs are uniquely poised to see and understand recurring phrases and metaphors that were in common use and instantly understood and contextualized by contemporary audiences.

In the absence of songs complete with identifiable written music from Shakespeare’s time, modern academics have attempted to fit lyrics to well-known historical melodies that would have been pressed into service at a given performance. In one particular case of academic absurdity, a computer was employed to compile lyrics as elements of meter, line count, and syllables in an attempt to match the meter of Elizabethan ballad tunes. As is the case with any attempt to turn living, breathing art into data points, the result of this attempt was, at best, unsatisfactory.

To understand how historical musicians would have responded to the practical need for music to fit lyrics, one must first be a musician. Then the musician must understand the use of music in historical theater; how to support the dramatic or comedic function of a song within a given scene, for a given production, in a given theater space, for a given audience. Absent this practical understanding, modern academics can and do promote unfortunate misconceptions of historical music in Shakespeare.

Modern composers have been inspired to create music for the many orphan song texts in Shakespeare’s plays, resulting in some wonderful compositions that stand on their own apart from the theatrical context. In historical practice, a musical setting that showcases the deep, subtle, cerebral meaning to be mined from Shakespeare texts was less meaningful to the circa 1600 theater audience than was effective music that supports the words and the dramatic action. For this reason, original productions of Shakespeare plays would have featured music that would serve the purpose in a noisy outdoor theater for performances that likely included extemporaneous action and music that could be easily adapted to the moment. But for indoor productions, more intimate music was possible, and that is where music for voice and lute enters the picture.

Shakespeare’s Lutebook

The music on our album is the result of decades of research and many lecture-recitals performed across the US, with publication of a book of scores bearing the same title, Shakespeare’s Lutebook.

We do not pretend to know whether Shakespeare the playwright played the lute—or whether the historical figure of Shakespeare the playwright existed at all. But we know that the plays were a collaborative effort written and produced in concert with several of the best literary and musical figures of the Elizabethan/Jacobean age, and indication for music in Shakespeare plays was as ubiquitous as any other stage direction.

Much of the music appearing in the plays is of a lighter character, suitable for capering and jollification in an outdoor theater. But the historical music Mignarda chooses is typically of a more complex nature, and was likely performed in an indoor theater where subtlety and nuance, an essential characteristic of music for voice and lute, might actually be heard. Our approach is to convey the texts with understanding, choosing historical musical settings when they survive, but employing informed choices of historical style and convention when the original setting is lost to history.

Shakespeare’s Lutebook is a personal selection of music drawn from some of the most iconic plays, and we share our interpretations to offer listeners our informed insights into the music common to Shakespeare’s time.

We are pleased to announce that “Farewell dear love” from the album Shakespeare’s Lutebook on the Prima Classic label is now available for streaming and download. This is the final release in a sequence of selected individual tracks from the digital album, which will be fully released on digital platforms March 1, 2024.

The setting of the [anonymous] text is by Robert Jones (c. 1577 – 1617), who was probably the most prolific English composer for voice and lute during the golden age of the form (1596 – 1622), with six published books of lute songs—and a set of madrigals stuffed with maniacal musical attempts at imitating bird songs.

“Of all the song composers of this brilliant period no one has been more completely or more unaccountably neglected than Robert Jones composer of ayres and madrigals, theatrical manager, and controversialist.“

– Peter Warlock, from The English Ayre, 1926

Little is known about Robert Jones but, given his connection with Shakespeare, he was surely associated with theater types and may have been related to an actor/musician named Richard Jones, about whom a bit more information survives. There is speculation that Robert Jones may have been involved in training child actors, etc., but the evidence is thin. Jones’ publication of a rather considerable amount of music, a costly and highly regulated endeavor, leads us to believe that he had solid connections and generous financial patronage.

Jones’ song “Farewell dear love” was published in The First Booke of Songes and Ayres, 1600, and the song must have been known to Shakespeare as a ballad that Jones presumably set to music and embellished with lute accompaniment, and with an arrangement for four voices. The song appears as “Farewell dear heart” in Act II : scene iii of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, or What You Will, published in the First Folio, 1623, where alternate lines are sung as a bit of fun by Sir Toby Belch and Feste the Clown as Malvolio is taking his farewell. As the text appears in the play—aside from the substitution of “heart” for “love” in the first line—the snatches sung by the two characters borrow text from both the first and second stanzas of Jones’ published setting.

“Farewell dear love” must have achieved popularity because the very same music appears among a set of other English tunes arranged as a lute solo on page 9 of Nicolas Vallet‘s Second Livre de tablature de luth (first) published in 1616, with the Dutch title “Slaep soete slaep” (NB: the melody bears no resemblance to the Dutch lullaby, “Slaap kindje slaap”). Vallet (c. 1583 – 1642), an expatriate Frenchman living in the Netherlands, was something of an anglophile, and had occasion to rub elbows with the many English actors and musicians touring the Continent. It is documented that Vallet formed a working quartet of lutes with three Englishmen, and it’s quite likely that he picked up Jones’ music from this source.

Jones published his First Booke in 1600, but the first serious book of English lute songs was published in 1597 by John Dowland (1563 – 1626), initiating a trend and providing a model that was emulated by a handful of contemporary lutenist/composers. Dowland appears to have had a very secure sense of self-worth, a condition that invited criticism by rivals jealous of his elevated skill and reputation. We offer an example of Dowland’s “humble-boasting” from his first published book:

“Thus hauing spent some moneths in Germany, to my great admiration of that worthy country, I past ouer the Alpes into Italy, where I founde the Cites furnisht with all good Artes, but especiallie Musicke. What fauour and estimation I had in Venice, Padua, Genoa, Ferrara, Florence, & diuers other places I willingly suppresse, least I should in any way seeme partiall in mine owne indeuours.”

– John Dowland, The First Booke of Songes or Ayres, 1597

It is not too difficult to surmise that Robert Jones was addressing Dowland in Jones’ introductory remarks in his own First Booke:

“Gentlemen, since my desire is your eares shoulde be my indifferent iudges, I cannot thinke it necessary to make my trauels, or my bringing vp arguements to persuade you that I have a good opinion of my selfe, only thus much I will saie: that I may preuent the rash iudgements of such as know me not.”

– Robert Jones, The First Booke of Songes or Ayres, 1600

Jones was obviously reacting to Dowland’s words, and he carried the rivalry further by expanding on the theme and hurling pointed insults at Dowland in his introduction titled “To all Musicall Murmurers, This Greeting” in Jones’ 1609 book, A Musicall Dreame:

“Thou, whose eare itches with the varietie of opinion, hearing thine owne sound, as the Ecchoe reuerberating others substance, and vnprofitable in it selfe, shewes to the World comfortable noyse, though to thy owne vse little pleasure, by reason of vncharitable censure. I speake to thee musicall Momus, thou from whose nicetie, numbers as easily passe, as drops fall in the showre, but with lesse profite.”

– Robert Jones, A Musicall Dreame, 1609

As Peter Warlock suggested, Jones may have been under-rated both in his own time and in his historical reputation today, but for compositional skill in music for voice and lute, none could hold a candle to that of John Dowland, whose forward-looking blend of melodic phrasing and harmonic language was cleverly integrated with the age-old use of counterpoint and melded with his understanding of the resources of the lute. Having just completed recording our second album for Prima Classic, we will have ample opportunity to delve more deeply into Dowland’s songs in the very near future.

Our recording of Robert Jones’ “Farewell dear love” is a prime example of authentic theater music from Shakespeare’s time, and it is now available for streaming and download through the usual digital providers of music.

We are pleased to announce that “Orpheus with his lute” from the album Shakespeare’s Lutebook on the Prima Classic label is now available for streaming and download.

Shakespeare’s play, The Famous History of The Live [sic] of King Henry the Eighth was published in the First Folio in 1623. Current scholarship reveals the original title of the play may have been All is True, and that John Fletcher (1579 – 1625) collaborated on this play with the acknowledged author. The play was shamelessly devised to invent a favorable backstory for the Tudor dynasty, and records show that it was performed on June 29, 1613 at the Globe Theater, but the performance was not completed: At the end of Act I, Henry VIII is meant to make an entrance with a celebratory cannonade, but sparks from the cannon set the theater’s thatched roof on fire, interrupting the play well before the third act—and before performance of our featured song that describes Orpheus and the power of music.

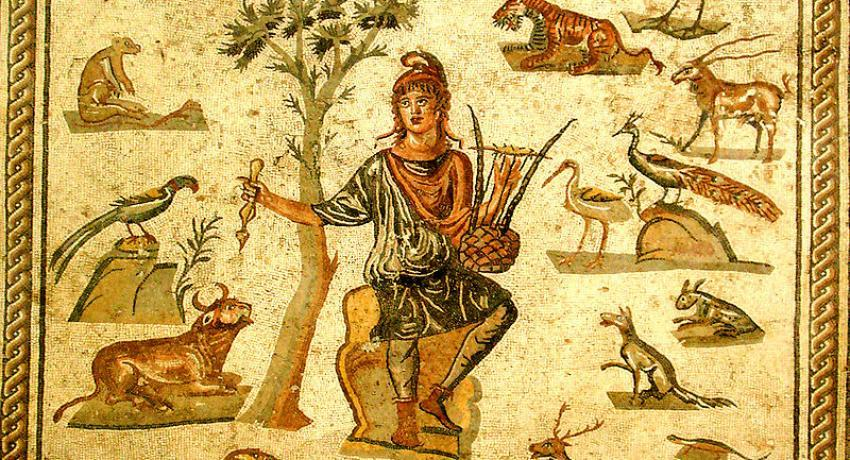

The myth of Orpheus and his lute : Orpheus, son of Apollo and the muse Calliope, was endowed with extraordinary musical skill, and when he sang and played all nature would become entranced, even the trees and stones. Orpheus met the love of his life, Eurydice, but soon lost her after she was bitten by an awful, dreadful snake. The devastating loss caused Orpheus to cease his music, but eventually there was a deal made that he could retrieve Eurydice from the underworld on the condition that, when exiting, he would not look back upon her face. This did not work out so well and Eurydice was snatched back to the underworld, and Orpheus was condemned to roam until he met an unfortunate end at the hands of the team on the Isle of Lesbos. Things happen.

The tale of Orpheus was well known among 16th- and 17th-century literati, whose education drew upon stories by Virgil and Ovid. The English lute composer, John Dowland (1563 – 1626), known throughout England and Europe as the preeminent songwriter of his age, was favorably compared to Orpheus, with the dedication of a lute pavan composed by the noble Moritz, Landgrave of Hesse “in honorem Johanni Dowlandi Anglorum Orphei” (in honor of John Dowland, English Orpheus).

Shakespeare’s song lyric in Henry VIII describes the power of music and treats as fact the use of music to ease one’s cares, as aptly described in Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy.

“But to leave all declamatory speeches in praise of divine music, I will confine myself to my proper subject: besides that excellent power it hath to expel many other diseases, [music] is a sovereign remedy against despair and melancholy, and will drive away the devil himself.“

To contextualize our song in Shakespeare’s play, at the end of Act II, Queen Catherine of Aragon pleads with Henry VIII and Cardinal Wolsey to not divorce and cast her out. As the third act begins, the Queen commands her servant, “Take thy lute, wench. My soul grows sad with troubles. Sing, and disperse ’em if thou canst.”

Orpheus with his lute made trees,

And the mountain-tops that freeze,

Bow themselves, when he did sing:

To his music, plants and flowers

Ever sprung; as sun and showers

There had made a lasting spring.

Everything that heard him play,

Even the billows of the sea,

Hung their heads, and then lay by.

In sweet music is such art:

Killing care and grief of heart

Fall asleep, or, hearing, die.

While no original music for the song survives from Shakespeare’s time, the text was later set to music by such composers as Maurice Greene (1696 – 1755), Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842 – 1900), Eric Coates (1886 – 1957), and Ralph Vaughn Williams (1872 – 1958). It is fairly safe to say that these settings are representative of their era and the sometimes virtuoso aesthetic of the particular composers’ time, and absolutely none of the musical settings would serve to actually lull a person to sleep.

Our musical setting of the text is newly composed in an informed period style. The fact that so many songs in Shakespeare plays do not identify the music points to the obvious: There was no need to identify the music because musicians of the period were perfectly capable of extemporizing a musical setting for any given text. Musicians were trained in the use of formulaic grounds (sets of chord changes) used to accompany a particular poetical meter, and also drew from a stock of well-known ballad tunes. There are surviving examples of this commonplace practice in English poetical anthologies like Tottels Miscellany (1557), where some poems are suggested to be sung to commonly-known ballad tunes. In our case, the newly composed musical setting was devised following the principles outlined in Thomas Campion‘s Observations in the Art of English Poesie (1602), Samuel Daniel’s response to Campion in A Defence of Rhyme (1603), and Sir Philip Sidney’s posthumous The Defence of Poesie (1595)

Our setting of “Orpheus with his lute” composed by Ron Andrico looks back to the tradition and style of theater music of Shakespeare’s time, and also honors the function of the song in the context of the play, and is now available for streaming and download through the usual providers of music.

Twenty-one years ago when we met and formed duo Mignarda, we knew from the beginning that we had little interest in identifying as yet another fleeting and very temporary lute-voice duo performing off-the-shelf lute songs and then just evaporating after using up that repertory. While our concentration was firmly rooted in early music, we did not identify with the (sadly) very corporate and quite cliquish early music scene in the US. The fact that we ignored the irritating gatekeepers and just went about creating our own audience gave us a sense of real connection with real people, and a glow of satisfaction that our music was touching people with honesty and directness: Our music is authentic in the truest sense.

While Donna developed her taste and technique from years of complete immersion in choral music, I (RA) previously played a variety of music from folk and country to lounge music featuring old jazz standards. After putting in the hard work of developing our repertory as duo Mignarda, at some point there was a small shift in the music we played together for enjoyment at home, and we began to perform what we call Heart-Songs, mostly parlor songs popular around the turn of the 20th century. When we were asked to perform this repertory, we came up with the name, Eulalie, an old-fashioned name that was the subject of a sentimental poem by Edgar Allan Poe and a song by Stephen Foster—and a name that featured prominently in the character of Sir Roderick Spode.

During the early days of the pandemic, we took the opportunity to record some of this alternative repertory and the result was the album Heart-Songs, released in 2020. As usual, we did nothing to promote the album, but it was somehow noticed by Thomas Hilton of Aldora Britain Records. Thomas, an enthusiastic advocate of independent music and artists, expressed an interest in our album and contacted us for an interview. The result was a six-page spread published this week in his E-zine that features a variety of other interesting artists from around the globe.

You can read an excerpt of the E-zine that includes just the table of contents and our interview here, and you can find the entire E-zine here . And if you want to know more about Eulalie, visit our website : https://www.eulalie.co/

We are pleased to announce that “Galliarda Romanesca” from the album Shakespeare’s Lutebook on the Prima Classic label is now available for streaming and download.

The galliard is a triple-time dance of Italian origin that was immensely popular for the span of perhaps 120 years. The name of the dance is from the Italian, gagliarda, meaning vigorous—but not necessarily fast. The depiction at the top of the page portrays Queen Elizabeth I, who was said to have danced five or six galliards every morning when she was in her fifties. Now that’s a senior power workout.

While there are passing poetical references to the galliard as early as 1490 in Orlando Innamorato by Matteo Maria Boiardo, early printed forms of the dance appear as “dance suites” with paired pavannes and galliards devised on the same melodic themes, the pavanne being in duple time and the galliard a triple-time variant. However, pavannes and galliards without thematic unity were printed separately in Pierre Attaingnant’s collection for lute, Dixhuit Basses Dances, 1530, predating the later convention of creating a thematic pair of dances. The independent galliard printed on folio 28 of this collection represents one of the very earliest appearances of the Romanesca ground.

The example of the Galliarda Romanesca on our recording comes from Luculentum theatrum musicum, Leuven (1568), from the printing press of Pierre Phalèse (c. 1510 – 1575), a Flemish printer, publisher and bookseller. The piece appears to be paired with the preceding “Padoana Romanisca” and is titled “La Gailliarda” on folio 81 of the book. The piece, which we call “Galliarda Romanesca,” consists of six sprightly triple-time variations on the Romanesca ground, and in concert we like to use the piece as a palate cleanser following the so-familiar song, “Greensleeves.“

According to 16th century descriptions, the galliard should probably be played at a much slower tempo than some hyperactive modern lute players may like. Thoinot Arbeau in his dance manual, Orchésographie (1589), described the proper tempo for dancing: “La gaillarde se dance [sautes] haulte d’une mesure plus lente et pesante.” (The gaillarde [jumps] high in a slower and heavier measure.) By the 1620s, the galliard had waned in popularity and ceded its position to the Courante. Having literally lost its vigor, Thomas Mace in his Musick’s Monument (1676) described the galliard as “perform’d in a Slow, and Large Triple-Time; and (commonly) Grave, and Sober.”

Our measured yet rhythmically punctuated recording of “Galliarda Romanesca” appears on our recording, Shakespeare’s Lutebook.